Alberto Rodríguez-Quiroga, M.D.; Ph.D., Miguel Ángel Álvarez-Mon, M.D.; Ph.D., Cristina Banzo-Arguis M.D.; Ph.D. , Aurelia María Matas Ochoa M.D., Patrícia Ángela Nava García M.D., Raquel Martinez de Velasco Soriano M.D., Fernando Mora Mínguez M.D.; Ph.D., Javier Quintero M.D.; Ph.D.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced a change of perspective in mental health professionals. COVID-19 leads to a full cascade of stress responses, causing activation of the endocrine stress axis at several levels and the production of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, as in many mental illnesses. The main objective of the study is to describe the profile of patients with COVID-19 infection attended by the Psychiatry Service during the first wave.

An observational, retrospective study, based on a sample of patients who were admitted due to infection with COVID-19 was carried out. Clinical data was extracted from the medical records. 71 Individuals with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and who were attended by a psychiatrist were recruited from an inpatient hospital in the metropolitan area of Madrid, Spain.

93% of the sample had a psychiatric diagnose, being adjustment disorder (44%) the most frequent. There was a significant association between a previous psychiatric history and a specific consultation on drug interaction with drugs used to treat COVID-19 and psychiatric medication (P=0.0036) and the use of corticosteroids and the need to prescribe psychiatric treatment (P= 0.012).

The current study suggests that specialists showed great concern for the possibility of drug interactions and that the use of corticosteroids predicted the need of further psychopharmacological treatment in COVID-19 patients. Keywords: COVID-19, Sars-CoV-2, drug interaction, corticosteroids, inflammatory parameters.

As COVID-19 has spread worldwide, there has been increasing recognition of the psychiatric implications (1). The pathogenic mechanisms related to neuropsychiatric manifestations in patients with COVID-19 are currently unknown. Different pathways have been proposed to affect the Central Nervous System (CNS): through direct infection of the CNS by the virus or indirectly through an immune response, an acute toxic encephalopathy associated with severe systemic infection or a medical treatment(2, 3).

Approximately one-third of patients with COVID-19 develop neuropsychiatric symptoms, including headache, paresthesia, and disturbed consciousness, and these symptoms seem to be associated with more severe form of disease(4). Patients with previous coronavirus infections, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) had neuropsychiatric manifestations, such as aggressive outbursts and other symptoms like confusion (27.9%), depression (32.6%), memory impairment (34.1%) insomnia (41.9%) and occasionally steroid-induced mania and psychosis (0.7%)(2, 5, 6). Suggestive signs of delirium, especially in the acute stage of SARS, MERS and COVID-19 have been systematically identified(2, 7). Previous influenza pandemics have been associated with long-lasting neuropsychiatric consequences, so it is possible that other large-scale viral infections, such as COVID-19 pandemic, will cause neuropsychiatric morbidity as well(2).

There is growing evidence that COVID-19 may lead to a full cascade of stress responses, causing activation of the endocrine stress axis at several levels(8). The stress system involves different pathways in which both the brain and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) play an important role. The dysregulation of this system can lead to morphologic changes in target organs or epigenetic stem cell changes, which might contribute to the development or exacerbation of different psychiatric disorders(8). During the first wave of the pandemic, there were numerous studies assessing, both efficacy and side effects of different treatments for COVID-19, most of them showing great interaction with psychopharmacological treatment(9).

Recent work has shown various pathways by which peripheral cytokines can either directly cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) or indirectly send signals to the brain through other substances, making it able to integrate and regulate many aspects of the acute phase response and exhibiting many local inflammatory responses that appear to contribute to both acute and chronic CNS disease(10). There is a link between mood disorders and inflammatory cytokine levels, in which the proinflammatory cytokines, responsible for the acute phase response, act on the brain to induce depression(11). Regarding COVID-19, the “cytokines storm” involved in the immune response could be contributing to the development of psychiatric symptoms by precipitating neuroinflammation(12). A recent study in COVID-19 survivors has proven that the immune response and systemic inflammation was positively associated with scores of depression and anxiety at follow-up(13).

The hypothesis of this study is that, in a sample of COVID-19 patients, attended by the Psychiatry Service during the first wave, corresponding to the months of March, April and May 2020, there will be an association between the severity of the illness (assessed with days of admission or need of Intensive Care) and greater severity of psychiatric illness (assessed with the diagnoses or the need for psychopharmacological treatment). The main objective is to describe the profile of patients with COVID-19 infection attended by the Psychiatry Service during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This was an observational, retrospective study, based on a sample of patients admitted to the hospital due to infection with COVID-19, between the months of March and May 2020. All of the data was extracted from the medical records. 71 Individuals with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and whom a psychiatrist attended were recruited from an inpatient hospital in the metropolitan area of Madrid, Spain. Inclusion criteria were the following: 1) Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 with the COVID-19 reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique admitted to hospital and evaluated by the Psychiatry Service. Exclusion criteria were: 1) Patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria. The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and ensuring compliance with the protocols and standards of Good Clinical Practice. Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee.

All of the information was obtained from clinical records. The following clinical and biological variables were collected: age, sex, previous psychiatric history, admission to Intensive Care Unit (ICU), d-dimer at the time of admission and at the time of discharge, C-reactive protein (CRP) at the time of admission and at the time of discharge, interleukin 6 (IL-6), ferritin, treatment with hydroxychloroquine, corticosteroids or tocilizumab, psychiatric diagnose, the need of a psychiatric treatment and days of admission. Data on ferritin and IL-6 was scarce in relation to the rest of the clinical variables, since they were not routinely requested in clinical practice until some weeks had passed since the start of the pandemic outbreak and there was more knowledge about the course of COVID-19. Psychiatric diagnoses were categorical DSM-5, based on one or various clinical interviews with the patient and in comorbid conditions; the most severe disorder was taken into account.

The qualitative variables were expressed by frequency distribution and quantitative variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Subsequently, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS test) was used to determine the distribution. Student t test or nonparametric Mann-Whitney U was used for comparison between groups of quantitative variables. In the case of qualitative variables, comparisons between groups were assessed using chi-square test. To examine the differences between various groups the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Correlations between different continuous variables were analyzed using the Pearson test.

For all these tests, the level of significance was 5%. The data analysis was performed using the SPSS version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

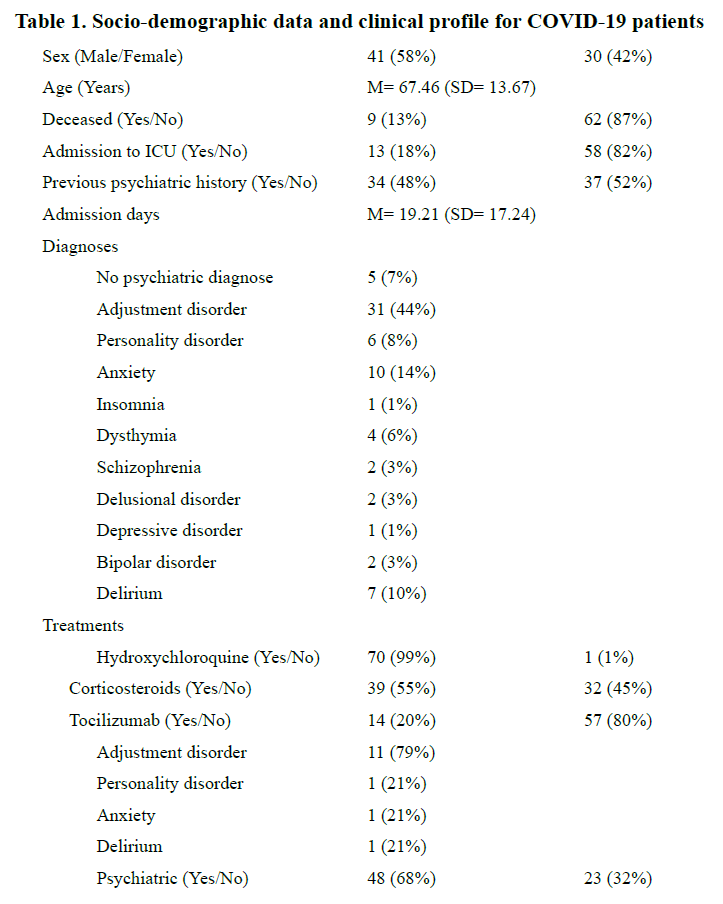

The socio-demographic characteristics and clinical data of the sample are shown in Table 1. 58% were males, 87% survived COVID-19 and 52% had not previous psychiatric history. 93% of the sample received a psychiatric diagnose, being adjustment disorder (44%) the most frequent. 99% of the patients received treatment with hydroxychloroquine, 55% with corticosteroids, 20% with tocilizumab and 68% were prescribed psychiatric treatment . 7 (10%) of the referrals from specialists were made to assess drug interactions. The variables that showed a statistically significant association were having a previous psychiatric history and a specific consultation on drug interaction with drugs used to treat COVID-19 and psychiatric medication (P=0.0036) and the use of corticosteroids and the need to prescribe psychiatric treatment (P= 0.012).

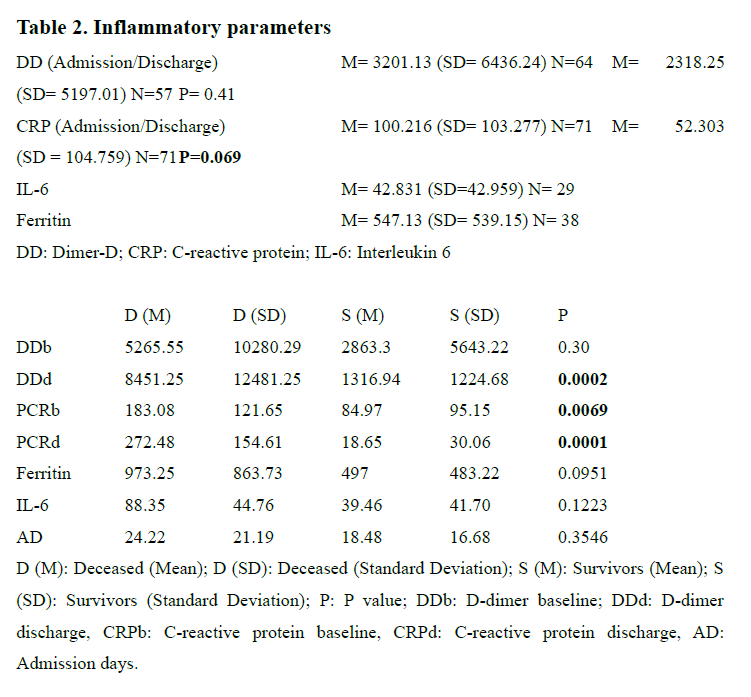

The data of inflammatory parameters is shown in Table 2. Statistically significant differences were only observed in CRP at the time of discharge compared to CRP at the time of admission. The sample was then divided into two groups: deceased patients and survivors. There was a significant difference in DD at discharge (P= 0.0002) and CRP, both at baseline (P= 0.0069) and at discharge (P= 0.0001).

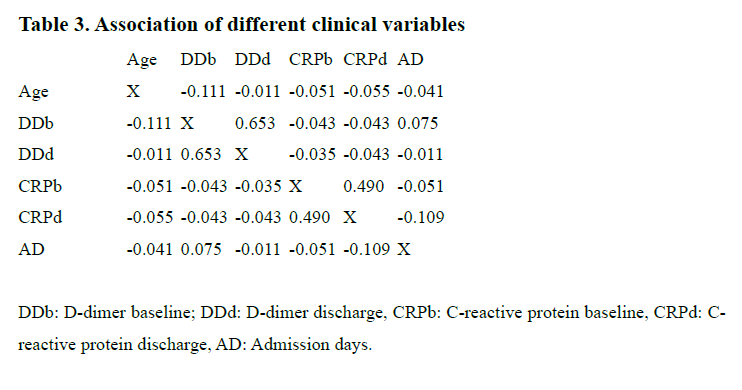

Table 3 shows the levels of correlation of different variables. Only DD at baseline and DD at the moment of the discharge from the hospital and CRP at baseline and CRP at the moment of the discharge from the hospital showed a moderate and positive association (R2= 0.653; R2= 0.490).

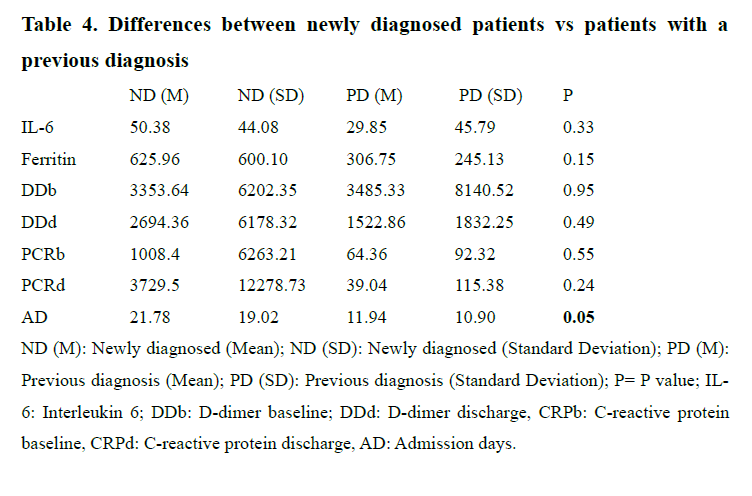

The sample was then divided into three groups: Patients with no psychiatric diagnose (N= five=, patients with a new psychiatric diagnose (N=50) and patients with a previous psychiatric diagnosis that remained stable after the evaluation performed by the psychiatrist (N= 16). A Kruskal- Wallis test was used to assess the differences between groups of DD and CPR, both at baseline and at discharge, but no statistically differences could be found. When comparing the group of newly diagnosed patients vs the group of patients with a previous psychiatric diagnosis that remained stable, only admission days showed a statistically significant difference (Table 4).

Our sample represents all of the patients admitted to a hospital in a metropolitan area of Madrid, during the first wave of the pandemic in Madrid, Spain, who were referred to the Psychiatry service. As expected, we reported high rates of psychopathology (93%). Our findings are in line with other studies assessing the psychiatric impact of the COVID-19(12,13).

The high rates of psychiatric disorders in our sample can be explained by different circumstances. To begin with, a first screening was carried out by other specialist, who consulted with the Psychiatry Service and only referred patients who were who were displaying psychiatric symptoms. We have already stated that the neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 are likely to be multifactorial and could be due both to the direct action of the virus and the indirect immune response, cerebrovascular disease or by the emotional response. The most frequent diagnosis was adjustment disorder, understood as a disproportionate emotional, cognitive or behavioral reaction to an event perceived as adverse. Acute psychological stressors such as social isolation, psychological impact of a novel severe and potentially fatal illness, physical discomfort, medication side effects, negative news on social media, concerns about infecting others and stigma (2, 13, 14) could have been acting like stressors in our sample. These results are in line with those of a meta-analysis of patients with COVID-19, in which depressive symptoms and anxiety occurred in 35% and 28% of them(15). Besides, some of the long-term effects of psychotropic medication (such as metabolic syndrome with long-term antipsychotics), comorbid physical health problems and smoking habits could make people with a mental disorder more vulnerable to COVID-19 (16)

Corticosteroids have been associated with adverse psychological side effects (APSE), ranging from psychotic symptoms to mild changes in mood and cognition(17). This is relevant, because there was a significant association between prescribing corticosteroids for the treatment of COVID-19 and the need for a referral to a Psychiatrist and the need for psychopharmacological treatment due to mental symptoms.

Increased levels of various cytokines have been found in different psychiatric disorders(18-20), something that also happens in patients with the SARS-CoV-2 infection(21). Thus, the immune system plays an important role, both in SARS-CoV-2 infection and in mental illnesses21. Higher serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6) have been found in SARS patients with severe disease(22) and in SARS-CoV infection (23), where a significant increase in the combined detection of IL-6 and DD could be a potential biomarker to identify early stages or the prognosis of the COVID-19 disease(24). In our study, patients in which COVID-19 was fatal, higher levels of DD at discharge and higher levels of CRP both at baseline and at discharge were found compared to survivors. We failed to replicate findings from a previous study of patients with SARS, in which the authors found an association between the severity of symptoms and some psychiatric outcomes(25). A recent review also found that patients with preexisting psychiatric disorders reported worsening of psychiatric symptoms (16), something we did not assess directly. Surprisingly, newly diagnosed patients had higher admission days to hospital compared to patients with a previous psychiatric history, suggesting the idea that the appearance of mental symptoms in patients infected by COVID-19 increases the mean length of hospital stay, perhaps because it represents an added stress factor to the disease itself, compared to patients with previously known chronic mental illness.

The study has several limitations. To begin with, some of the variables that contribute to neuroinflammation and directly influence both the natural history of COVID-19 and the associated psychiatric outcomes, were not taken into account such as age (26), obesity or a previous history of autoimmune diseases (27). However, since the purpose of the work was to describe a sample of patients, this should not hamper the interpretation of the results. Another limitation was that we could not collect some of the data for all of the patients, particularly, ferritin and IL-6. The low sample size in both variables may explain why we were unable to find statistically significant differences in the different patient populations. This was due to the continuously changing protocols of COVID-19, in which the extraction of ferritin and IL-6 did not begin until a few weeks had passed. The main limitation is that the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow interpretation for causality.

The current study suggests that the inflammatory response, present in the more severe cases of COVID-19 and in some psychiatric disorders, could be a shared link between both disorders. In the acute phase of COVID-19, adjustment disorder was the most common psychiatric disorder in hospitalized patients, due to different factors, such as isolation, generalized feelings of hopelessness, uncertainty, and fear, triggered by the psychological impact of a novel severe and potentially fatal illness, physical discomfort, medication side effects, negative news on social media, concerns about infecting others and stigma. Thus, the SARS-COV-2 pandemic could connect systemic infection to neuropsychiatric diseases.

We would like to thank all of the patients who suffered from COVID-19 and to all health workers who were involved, directly or indirectly, in this pandemic.

The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and ensuring compliance with the protocols and standards of Good Clinical Practice. Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee. This study did not receive any kind of funding. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare related to the content of this study.

1. The Lancet Psychiatry. Send in the therapists?. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7(4): 291.

2. Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7: 611–27.

3. Klein RS, Garber C, Howard N. Infectious immunity in the central nervous system and brain function. Nat Immunol. 2017; 18: 132–41.

4. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M et al. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020; 77: 1–9.

5. Kim HC, Yoo SY, Lee BH et al. Psychiatric findings in suspected and confirmed middle east respiratory syndrome patients quarantined in hospital: a retrospective chart analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7: 611–27.

6. Jeong H, Yim HW, Song YJ. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East respiratory syndrome. Epidemiol Health. 2016; 38: e2016048.

7. Beach SR, Praschan NC, Hogan C et al. Delirium in COVID-19: A case series and exploration of potential mechanisms for central nervous system involvement. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020; 65: 47–53.

8. Steenblock C, Todorov V, Kanczkowski W et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the neuroendocrine stress axis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020; 7: 1–7.

9. Wu R, Wang L, Kuo HD al. An Update on Current Therapeutic Drugs Treating COVID-19. Curr Pharmacol Rep. 2020; 11:1-15.

10. Ting EYC, Yang AC, Tsai SJ. Role of Interleukin-6 in Depressive Disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21: 2194.

11. Orsini A, Corsi M, Santangelo A et al. Challenges and management of neurological and psychiatric manifestations in SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) patients. Neurol Sci. 2020; 6: 1–14.

12. Dantzer R. Neuroimmune Interactions: From the Brain to the Immune System and Vice Versa. Physiol Rev. 2018; 98: 477–504.

13. Mazza MG, De Lorenzo R, Conte C et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 30.

14. Ingraham NE, Lotfi-Emran S, Thielen BK et al. Immunomodulation in COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 8: 544–6.

15. Kong X, Zheng K, Tang M et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Depression and Anxiety of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020.03.24.20043075

16. Smith K, Ostinelli E, Cipriani A. Covid-19 and mental health: a transformational opportunity to apply an evidence-based approach to clinical practice and research. Evid Based Ment Health. 2020; 23:45-6.

17. Stuart FA, Segal TY, Keady S. Adverse psychological effects of corticosteroids in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 2005; 90:500-6.

18. Rodríguez-Quiroga A, MacDowell KS, Leza JC et al. Childhood trauma determines different clinical and biological manifestations in patients with eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2020 May 18. [Epub ahead of print].

19. Grace AA. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016; 17: 524-32.

20. Fernandes BS, Karmakar C, Tamouza R et al. Precision psychiatry with immunological and cognitive biomarkers: a multi-domain prediction for the diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia using machine learning. Transl Psychiatry. 2020; 10: 162.

21. Raony Í, de Figueiredo CS, Pandolfo P et al. Psycho-Neuroendocrine-Immune Interactions in COVID-19: Potential Impacts on Mental Health. Front Immunol. 2020; 11: 1170.

22. Zhang Y, Li J, Zhan Y et al. Analysis of serum cytokines in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Infect Immun. 2004; 72: 4410–5.

23. Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; 71:762-8.

24. Gao Y, Li T, Han M et al. Diagnostic utility of clinical laboratory data determinations for patients with the severe COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2020; 9 2:791-6.

25. Cheng SKW, Tsang JSK, Ku KH et al. Psychiatric complications in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) during the acute treatment phase: a series of 10 cases. Br J Psychiatry. 2004; 184:359-60.

26. Zhavoronkov A. Geroprotective and senoremediative strategies to reduce the comorbidity, infection rates, severity, and lethality in gerophilic and gerolavic infections. Aging (Albany NY) 2020; 12: 6492–10.

27. Kappelmann N, Lewis G, Dantzer R et al. Antidepressant activity of anti-cytokine treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of chronic inflammatory conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 2018; 23: 335–43.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced a change of perspective in mental health professionals. COVID-19 leads to a full cascade of stress responses, causing activation of the endocrine stress axis at several levels and the production of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, as in many mental illnesses. The main objective of the study is to describe the profile of patients with COVID-19 infection attended by the Psychiatry Service during the first wave.